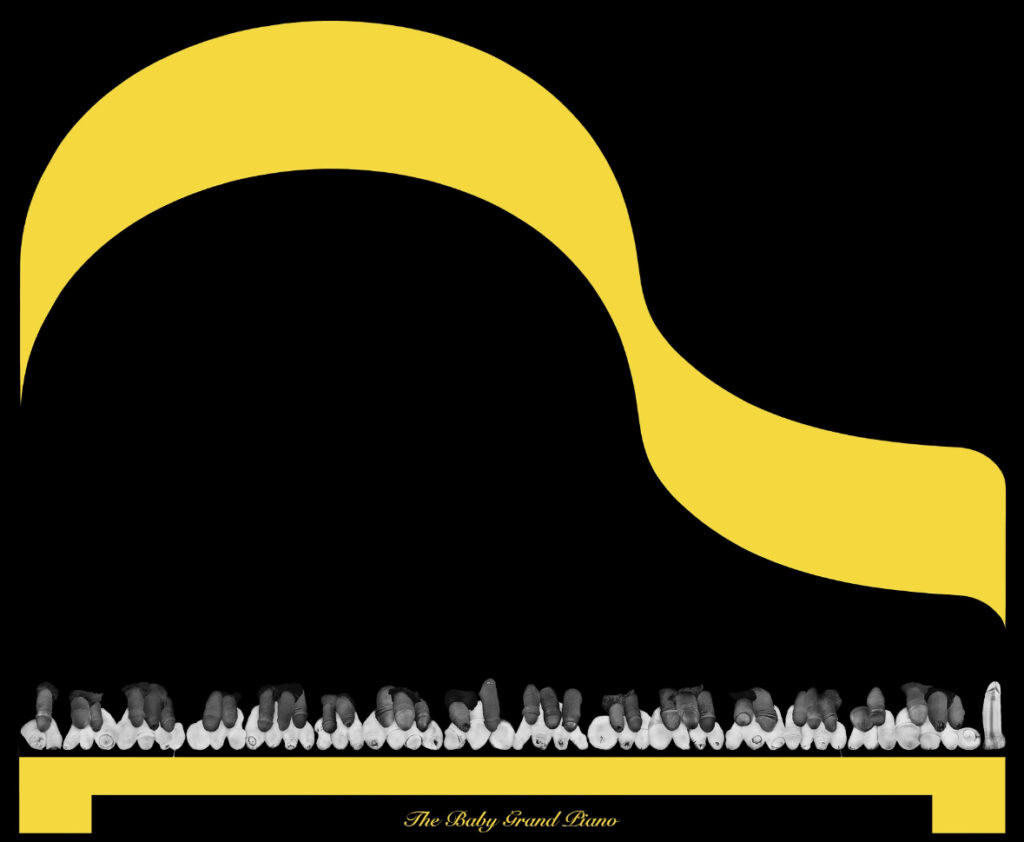

THE BABY GRAND PIANO

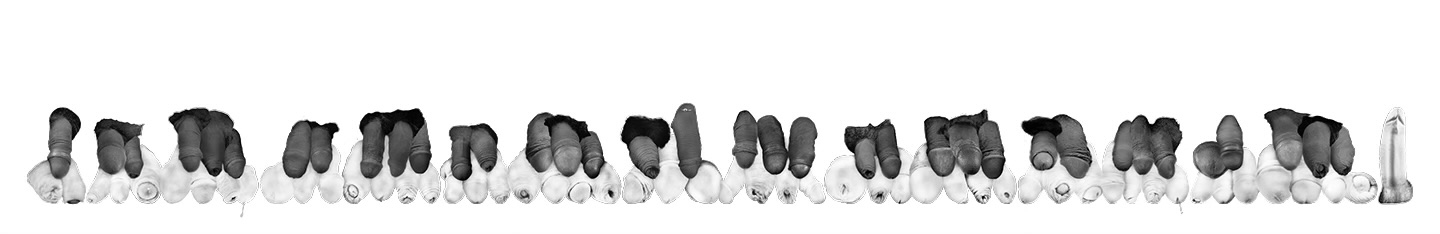

THE BABY GRAND PIANO – Detail

THE BABY GRAND PIANO – COLOR

The Baby Grand Piano is a photomontage of 88 penises (52 white and 36 black) photographed and digitally assembled to make a 72-inch piano keyboard. Karalla studied the construction of a piano, took some 20,000 photographs over a period of two years in Southern Italy and New York City, and built the 7 octaves of the instrument.

In The Grand Piano, Karalla explores a key taboo, the penis. Some societies tend to view the penis as ugly and something that should not be seen, touched or even discussed. The Grand Piano encourages both participant and viewer to re-examine their relationship to this powerful subject. Women played an unprecedented role in banding together and bringing their men to Karalla, while the men themselves – as the faceless donors – were freed of identity and class.

For the viewer The Grand Piano is an invitation to investigate not only personal but also cultural attitudes towards the penis, such as the question of circumcision, and the differences between rural Italy and urban America. Beyond that the work presents the viewer with a glimpse of prohibited knowledge, a forbidden fruit as timeless as that on the Tree of Knowledge that stood before Adam and Eve. As such it encourages, dares even, the viewer to experience a moment of transgression in seeing a taboo image presented in a new context. As Karalla herself says, “As an artist, I am constantly exploring the barriers that society imposes. I ponder what would happen if these restrictions were to lose their hold upon us. The Grand Piano is the result of this examination, through which I aim to create a community of transgression.”

Karalla works between the modern backdrop of New York City and the rural south of Basilicata, Italy. Between these two landscapes, the inhabitants participate in order for her projects to take on a life of their own. Heavily draped in the Catholic order, Italy intertwines with its opposite, the land of freedom, New York City; her projects bring the communities of people together. The participants that are involved are also challenged, questioning their beliefs, cultural upbringing and identity within their community.

The Baby Grand Piano – French Translation by Nathalie Bru

Pour les sept octaves d’un piano classique, comptez 88 touches (52 en ivoires et 36 en ébène), pour les sept octaves du Grand Piano comptez 88 pénis (52 blancs et 36 noirs). Il aura fallu deux ans à l’artiste New Yorkaise Cynthia Karalla pour parvenir à mettre en musique l’oeuvre qu’elle présente aujourd’hui.

Montage photographique composé d’une sélection de 88 images de pénis au repos, sélectionnés parmi plus de 20 000 clichés réalisés lors de prises de vues en Italie et à New York, le Grand Piano propose d’apporter de l’harmonie à la représentation personnelle et culturelle que nous nous faisons du sexe masculin.

La mise en musique de Cynthia Karalla nous aide à accorder réalité et fantasmes tout en nous confrontant aux méandres d’un tabou tenace de nos sociétés pourtant supposées libérées : le pénis. Parfois considéré laid, sommé de rester discret, de ne pas se montrer, de ne pas se laisser trop facilement toucher, le pénis n’anime que rarement les conversations de salon. Le Grand Piano nous convie donc aujourd’hui à réévaluer notre rapport à cette partie, cachée mais omniprésente, de l’anatomie masculine.

Dès l’amont des prises de vues, l’entreprise était déjà à l’oeuvre pour les 88 modèles ayant prêté leur concours et pour tous ceux qui ont préféré décliner l’offre de l’artiste. Intéressant, surtout, de noter que les femmes, tant en Italie qu’aux Etats-Unis se sont révélées des alliées de choix. Sans le concours de nombreuses épouses, fiancées, petites amies ou simples amies, de nombreuses prises de vues n’auraient pu aboutir.

Le Grand Piano nous demande d’affronter nos dispositions non seulement personnelles mais aussi culturelles vis à vis du pénis. Exempts d’identité et de classe sociale, les 88 éléments qui composent ce piano ne se différencient que par leur aspect objectif et leur réalité primitive ou altérée par l’intervention sur la chair (circoncision, piercing). Américains citadins, ruraux du Sud de l’Italie…la composition défie celui qui la regarde de trouver l’origine de chaque pièce qui la compose.

Au-delà encore, le travail de l’artiste lève un coin du rideau qui nous maintient à distance de la véritable connaissance du fruit défendu. Il défie celui qui passe de faire l’expérience d’un moment unique de transgression : une image tabou présentée dans un contexte tout à fait neuf.

“En tant qu’artiste, j’affronte en permanence les barrières que la culture nous impose. J’essaie d’imaginer ce qu’il adviendrait si ces barrières venaient à être définitivement levées. Le Grand Piano est le résultat de cette réflexion, à travers laquelle je vise à créer une communauté de transgression”

Depuis plusieurs années, Cynthia Karalla partage son temps entre le décor hyper-urbain de New York et la ruralité brute de Basilicata, en Italie du Sud. Dans un endroit comme dans l’autre, l’artiste fait en sorte de toujours mettre les habitants à contribution afin de permettre à ses projets de prendre vie et relief au-delà de la démarche artistique qui les a initiés. Dans son travail, la très catholique Italie fait corps avec son contraire, New York la ville des excès ; ses réalisations tissent des liens entre les deux communautés et invitent chacun des participants à réexaminer son système de valeurs, son éducation et son unicité dans le tout.

Alexander Nasarewsky on the Baby Grand Piano

Cynthia Karalla is an artist who works both in New York and Italy. Her piece “Baby Grand” is a multivalent commentary on our values, our assumptions, and our beliefs. At an individual level, Karalla problematizes such issues as circumcision. On a societal level, racism, homophobia, and the musical potential of piano itself are addressed. By presenting an assemblage labeled a piano, she problematizes the assumed uniformity of the keys, and the strong sense of cohesive forms. By creating an uneven distribution of keys, she brings attention to the social strife that exists between race and sexuality. Recent news issues such as 11 states approving constitutional amendments stating that marriage is exclusive to heterosexuals gives us insight into the climate of discrimination which is accepted by Americans everyday. By creating this assemblage of many different penises, she celebrates mankind’s diversity and shows that a resonant rhythm can be formed with so many different types joined together, unifying as a whole instrument.

In “Shock and Awe” named after the Bush administration’s offensive against Iraq after the September 11th attacks, we are confronted by a gloriously erect penis, aggressively standing above the rest. Semen drips out of the penis below it, in an orgasmic celebration of the male aggressive instinct driven by testosterone. The American militaries concept behind “Shock and Awe” is a focus on psychological destruction of the enemy, a tactic of fear whose intent is to control. It is based on destroying the enemies will to fight, using the fear of loud explosions as its agent. Karalla uses this tactic to illustrate the fear we have of confronting this bodily organ which contemporary American society goes to great lengths to cover it. Karalla wants the viewer to see that we are afraid of what is natural and should be celebrated for its beauty, not feared.

The fear of the penis comes from this, the subconscious fear of the potential of impregnation. The penis’s ability to bring future generations into this world is a powerful force. Why is an element, an essential life-giving organ that is a part of the human body and the human experience, shunned? Why do we find such a lack of aesthetic qualities of the penis? The penis refusing to submit to conventions of uniformity this is why a climate of fear surrounds it. Karalla attempts to dissipate the fear we have which is not innate, but one that has been manufactured and put into us, a system of control. Just like this country, and its fears of homosexuality, and race, fear is an invaluable element to control and manufacture agendas based on hate and discrimination.

If one quote is to give us insight into the nature of circumcision, Karalla’s cousin remarked after a discussion of the piece why she chose to circumcise her son. “Well, I want him to look like his daddy.” To maintain the status quo, systems of control are put into place, which utilize fear and manufacture a uniformity that becomes socially accepted. The uncircumcised penises stand out precisely for that reason. They do not submit to the ritualistic uniformity that we have grown accustomed to.

Karalla is a composer, who weaves these different notes, all producing an individual sound, by taken as a collective, producing a melody. The penises are erect and flaccid, circumcised and uncircumcised, black and white. Taking all of the diversity of men into account, Karalla weaves a sense of rhythm and fluid musical potential into an otherwise disjointed assortment of penises. Karalla shows us a world of possibilities, a world where the sole unifier is to celebrate our diversity not by engaging in ritualistic uniformity, such as a culture that circumcision produces, but to stand out as individuals who create a melody as telling of their own penile idiosyncrasies. Karalla describes the origins of this idea coming from a dream.

Karalla’s Statement on the Baby Grand

I bathe in the country’s political turmoil. As an artist, I am constantly re-examining the barriers that Culture imposes. I ponder what would happen if these restrictions were to lose their hold upon us. This seed grew into “The Baby Grand Piano.”

In 2004, the political climate was infused with fear. Before the re-election, Americans were bombarded with news of heightened terror alerts. “Fear” was a constant watchword. Like any four-letter word worth its salt, fear has the power to enslave.

Our culture enslaves us in many ways, some obvious, and some not so obvious. Women in America are taught from an early age that good girls are rewarded and bad girls — however that is defined in the local parlance — are punished (act locally punish globally). Fear is instilled in girls that if they don’t behave “like ladies,” they may end up as dead as the women in film noir and horror films.

The years since 9/11 developed into a period in which friends, family and lovers united only in one regard: disagreement. Like the artificial distinction between “good” and “bad” behavior, which creates its own disunity, the fear-mongering that has become prevalent since the terror attack has served no true purpose but to disunite us: Cross the line and die.

Coming from a strict Catholic background, the penis was taboo. It was in this context of fear and disunity that I made a piano keyboard, and each of the keys was a penis. Black penises for the black keys; white penises for the white keys.

I honestly wondered if I could do this project – where did the boundary lay and could I penetrate it without imperiling myself. But with the courage to cross the line one gains the courage to banish fear.

In a small town in the south of Italy, the women brought me their men to photograph. Once I was able to step over the imaginary line, I found that rather than being cast out, I was embraced. I was not “bad,” any more than someone too fearful to cross is “good.” The shooting of Baby Grand Piano became a celebration of the possibility that the fear was surmountable and that the taboo was just that. In my small corner of the world I was able to banish fear and create a community of transgression.

And yet the transgression is only the beginning. If the piano is only seen for that “transgressive value”, then it’s unique piano/organ music has not been heard. The work must be presented in all of its unsheathed glory so that its music may resonate.